I have a play in my head that has frightened me for a long time because it will require considerable research to write authentically—and the stack of books I’ve accumulated to begin the work is a bit intimidating. Not that I can’t read; I figured that out when I was six, but there is a gap between book knowledge and lived experience—and what will be required ultimately, is an avenue into the lived experience of individuals who struggle under constant scrutiny from the state. Now I have a great resource that I will talk about in future posts, but for now, let’s return to this fun little exercise:

Last week I wrote about Marsha Norman’s five sentences, in which you can get at the arc of a story by filling in these blanks:

- This is a play about _____.

- It takes place _____.

- The main character wants _____ but _____

- It starts when __________

- It ends when __________.

For purposes of the exercise, as well as this new play, I have filled in the blanks as follows:

- This is a play about a man whose ability to recall the most vivid and trivial detail of everything he ever saw or experienced is at first regarded as a medical phenomenon.

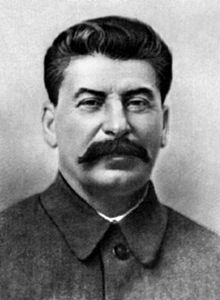

- It takes place in the Soviet Union at the time of Stalin’s purges.

- The main character wants to be rid of a traumatic memory, but soon discovers that his strange gift is a political liability for powerful people who have a strong need for certain events to be erased from public memory.

- It starts when he encounters a psychologist who says she can help him deal with his trauma.

- It ends when he convinces an agent of the secret police that his phenomenal memory is a mere circus act.

The five sentences give a sense of the story’s arc and allowed me to craft a short summation of the story as follows:

In 1930s Moscow, a man with a phenomenal memory is targeted by Stalin’s persecution machine when he is unable to forget an incident that undermines the official story about the fate of a high-ranking Soviet official.

So that is the elevator speech.

Now to write the play. I have at least 10 or 12 books to read and absorb and while I do that I will start noodling with exploratory scenes.

So the second part of the exercise is to write an opening scene as I envision it right now. I sketch out an encounter between the doctor and patient in which it is revealed that the patient not only has a phenomenal memory for vivid details, he recalls through image and odor and attaches sound to colors, tactile sensations to sound and colors to tastes.

Though synesthesia is a fascinating medical phenomenon, it is not a particularly interesting scene—too expositional—and because I don’t like to embarrass myself, I won’t post it. But to liven it, I will turn to an exercise from Michael Bigelow Dixon, former literary manager of Actors Theatre of Louisville and currently a professor of theatre at Transylvania University in Lexington, Ky. He is also obviously a brilliant mind because he once produced a play of mine.

Okay, so Michael gives us this exercise, and for more of the same, check out his book here. Yes, kids, you can try this at home:

Michael’s Step-up-the-Stakes Exercise

1. Put two characters who share something in common in a place neither can leave. And write a scene in which the obstacles and stakes are high and clearly presented.

Obviously, the patient can leave the doctor’s office if he wishes—unless it’s an office in a mental hospital, then perhaps not. But I don’t see that. He is not committed to a hospital; he’s out in the world. He has to be out in the world in order to experience the disconnect between what he observes—and what he is told to understand. However, since I know the state is interested in the patient, one high stakes scenario comes immediately to mind: An interrogator and his prisoner. Fairly obvious.

And what do they share?

Their mutual hatred of the Tsar.

And who are they? Not the patient and the doctor – but the doctor and an official who needs information about the patient. The doctor, then, is the prisoner.

That adds an interesting wrinkle, and I will share that scene next week.