The package that arrived in my mail in mid-January came as a surprise, not because it was unexpected, but because the contents were so much more revealing than I had imagined possible—nearly 70 pages of Photostats, detailing the movements of my late uncle Jack in the three years he spent in the Army Air Force during World War II. Jack’s records were largely intact, having survived a 1973 fire in the National Archives in St. Louis that had destroyed nearly 80 percent of the military records then on file.

What those records revealed was a short life far more troubled than I had realized.

My mother never spoke of this mysterious younger brother unless prompted by one of us, and even then her stories were spare and brief. What I knew of Jack was that he had been rebellious and bold and that he had died, in an apparent car accident, years before I was born. The few photographs we had of him showed a cheerful, friendly young face with a spark of mischief in his eye; it was left to us to fill in the details, and I did: in my mind he was reckless but sincere, good-hearted and kind, adventurous and noble—the kind of uncle every girl wanted, who would have taken me on long walks and imparted to me the wisdom he had gleaned from his years of unrest. He might have been a bit wild, but he was not a bad boy; he simply loved a good time and took nothing seriously. We knew this to be true; we could see it in his eyes.

But the picture that emerges from the documents is much different, much darker—a story of a troubled young man with a fondness for drink—who lost more than 100 days of service to his habit of leaving the base without permission—who married because he had to—and who died in the fall of 1946 by an unspecified cause. I knew the cause—I’d already gotten his death certificate—he died alone in October 1946, killing himself by putting his head in the oven and turning on the gas.

This sorry end was not reflected in the military documents, which showed that in spite of his spotty service record, he’d left the Army with a good conduct medal and a World War II victory medal (this, I presume, was standard issue to any veteran at the time).

According to the documents, Jack was not a good soldier. He got drunk in uniform, got into bar fights in uniform, fell asleep at his post—for which he was court-martialed twice—and went AWOL multiple times.

His medical records at discharge show that in the winter of 1943, he had been treated for a stomach disorder caused by drinking. At the time of discharge, he was severely deaf in his left ear, though no such disability was indicated when he enlisted. And the records reveal a “slight speech impediment.” A stutter perhaps?

None of these details is especially remarkable. At 5’ 9’, 152 pounds, this brown-haired, blue-eyed young man of Irish descent was thoroughly ordinary. Instead of the war hero I’d imagined, a fighter pilot on daring missions over Germany, he trained as a cook—later was assigned to the medic corps–and unlike my father, who spent time in Belgium and later in the South Pacific–Jack never left the states.

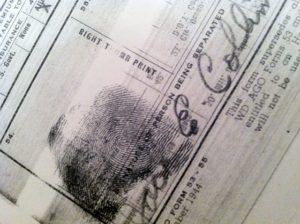

But even so, the sight of his signature and fingerprint on his enlistment form gives me chills.

Here is proof that the boy of legend had really lived and breathed, had struggled, suffered, failed, and somehow found love–if only for a time. There he was: in the ridges of his fingerprint, pressed into paper more than 70 years ago, more than an abstraction, more than a memory, more than a faded photograph.

Jack was real.

And strangely, somehow, that signature and fingerprint made him more real to me than any of the snapshots in my mother’s family album. The path of this lost boy was now in front of me, undeniable and sad, his trajectory of self-destruction reflected in his frequent infractions.

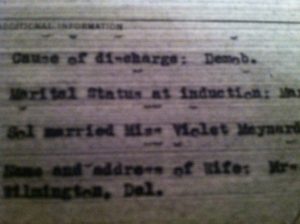

But the greatest shock of all arrived in a single line, on a request for burial benefits filed by his widow Violet in January 1948:

“Marital status at induction: Married. Sol. Legally divorced in May 1944.”

Violet was Jack’s second wife.

This revelation was literally breathtaking.

This revelation was literally breathtaking.

Just shy of 22 when he enlisted in the Army Air Force in the summer of 1942, Jack was already married to a girl in Springfield, Ohio. Less than two years later, he divorced her, and in February of 1945, he married Violet—six months before the birth of their daughter, Thelma Jeannette.

My parents had never mentioned this girl, who is identified in the records only as Norma Jean. Apparently they had no children—for there is no mention of any other dependent. How he met her, how long they had been together, and why they parted is not explained.

But Jack was stationed in Wilmington, Del., Violet’s home town, as early as 1943. The records show that Violet made her home in Wilmington, both before and after the war–and it is to her address, at 303 Shipley St., that Jack had directed his final paycheck to be delivered when he was discharged from the service. Clearly, he met her there, sometime in 1943 or 1944. And the record also shows that in November 1945, after Jack had been reassigned to a base in California, he went AWOL—only to be picked up a month later in Wilmington.

We can safely conclude he left California to see his wife and daughter. What crisis prompted his decision to leave the base without permission, we can only guess. I do know that my father told a story of opening the back door one cold day and being startled by the sight of a man’s head—just a head—gleaming pale in the early morning light. It was Jack, asleep on the stoop, with his military coat pulled over him for warmth, only his face visible.

Could it have been that my mother’s house in Pennsylvania was a stop on the way in that illicit trip East?

We are left with only questions.

How is it that Norma Jean never merited a mention? How is it that Violet never made an appearance—no effort to connect with her late husband’s family? Was she the cold, bad woman of my father’s description? Or was there another dimension to her story?

Jack married her out of duty, that is clear, but perhaps he also married her out of love and passion.

That love went quickly sour, but somewhere out there, very likely, his daughter still lives.

Can we find her? And if we do? What secrets might she reveal?