Late in September 1920, a notice appeared in the Springfield, Ohio, newspaper that the young wife of Bill Collins had died. The cause was edema, a complication of pregnancy that she might have survived had her caregivers not put her to bed—and thus ensured the onset of the pneumonia that took her life. The fluid that swelled her legs also filled her lungs. Feverish and weak, she passed away within a month of giving birth to her only son, my uncle Jack.

The death of Lola Blazier Collins cast a long shadow across three generations.

She was not yet 22 when she died, and she left a 15-month-old daughter, my mother. How that death affected her young husband is only now conjecture, but the evidence is apparent in family stories. He was surely bereft, surely guilt-ridden, as there is no question his passion for her was the proximate cause of her death. As my mother later told me, Lola’s family held him responsible, felt that he should have seen to it that, after a difficult and dangerous first pregnancy, she never had another.

Surely he blamed himself as well.

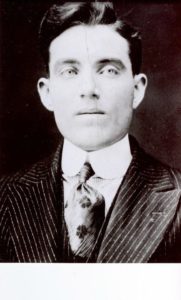

The fact that he later married, in good health, at the age of 30, a woman a year younger, and produced no further issue suggests to me that he carried that guilt with him the rest of his life—a crippling guilt that infected his second marriage and from which he found relief in drink. The evidence is right there, on his face, in the wedding photo from that second marriage. Bill stands to the far left, his bride on his arm, squinting into the sunlight; she smiles shyly and, I think, optimistically. The photograph is remarkable as a study in contrasts. Ten years have passed since his marriage to Lola; Bill looks like a man of 50. In reality, he is six months shy of his 31st birthday. And he is not smiling.

It strikes me as strange. These were good Catholics all—children were the very point of marriage, physical fulfillment only a happy byproduct—and yet no children were born from this second union. And very quickly, the woman Bill married to care for his young children became a step-mother of nightmares. My mother’s accounts were shocking to me when I first heard them—the bitterness in her voice (“She used to beat us!) —the stories of unprovoked cruelty (locking them in closets, going after them with a broomstick, taking away their toys). Years later, on a trip to Springfield, my sisters and brother and I came upon an old friend of my mother’s who corroborated her stories. Not that we had reason to doubt.

But what could have prompted such outbursts? Was Teresa merely unbalanced? A bitter almost-old maid schoolteacher who took her frustrations out on the nearest and most vulnerable scapegoats? Or was there a twisted kind of logic working behind her rages?

On the long drive up the winding avenue to the cemetery where we found Lola’s grave, it came to me:

It was jealousy.

Poor Bill could not let go. Lola’s memory stood between him and his angry second wife. And whether that led to outright physical dysfunction or merely a quiet understanding that Teresa could never be to him what Lola had been—she must have known that she was second best. And where to direct that jealousy except to those children who represented the very ghost that stood in the way of her own happiness?

This was not a time when people spoke frankly of such matters, nor sought out the advice of counselors or therapists. Frustrations like these almost always went underground, only to erupt in some sideways fashion, disconnected from the cause.

And how that played out in the fragile psyches of those children—poor lost Jack and his sister, my mother, whose emotional survival depended on closing off her heart to any kind of pain—and thus, to any kind of love—is a story for another day.

The long shadow of loss carried across the generations, from guilty father to guilt-ridden son and anguished daughter who later lost her brother to his own demons. This is the stuff of drama, but it is also all true: The mask of normality settles over a family, the children go to school, the parents work, hold the household together, dinner gets to the table on time, homework is finished, the dishes washed and dried—while amid and behind these ordinary routines the most extraordinary acts of cruelty take place. And because the adults in the household lack the courage to speak the truth—to see the truth—they retreat into the comfort of their own denial, leaving the children alone to make sense of the chaos in their hearts.

And few children are up to the task.

D.W.G.