“The strength of Gregory’s characterization of Judy is that she does not allow disability to become an all-encompassing character trait that merely paints Judy as either bitter or heroic. … In short, by using disability as a dramaturgical device rather than a metaphor, a stereotype, or an all-encompassing world-view, Gregory has made the play and Judy’s disability more accessible and approachable to a mainstream audience without diminishing the reality of disabled life for Judy.

–— Bradley Stephenson, Ph.D. candidate in theatre, the University of Columbia, Mo.

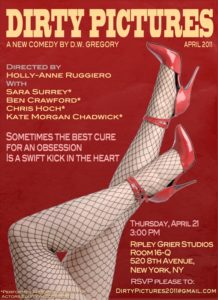

It is an odd sensation to find oneself the subject of study—and even stranger to discover that the examination will be shared at an academic conference. But let me wish Bradley Stephenson the best with his paper “Reclaiming Wholeness: The Dramaturgy of Disability in D.W. Gregory’s Dirty Pictures,” which he will present at the Association for Theatre in Higher Education (ATHE) Conference in Washington, D.C., Aug. 2-4. This is a project he’s been working on for several months—a final paper for a course he was taking at Mizzou on Women’s Dramatic Traditions—and I imagine it’s a pretty high stakes event for him, to present his work to his peers and superiors in this way. Most of the people in the audience are sitting where he aspires to, being university professors of theatre.

Speaking as someone who spent years making a living by writing about other people, I find it frankly kind of weird to read about my work through someone else’s eyes. But I’ve read the paper and I think Bradley has nailed it. I’m especially flattered by his conclusion that Dirty Pictures is “subversive.” That’s a word that applies very well to a play that presents a story in the familiar frame of sex comedy but goes on to upend the audience’s expectations of the characters. One actress who worked on an early reading said the play “explodes stereotypes.” I certainly hope so. So Bradley, I embrace your assessment of Dirty Pictures and I plan to use “subversive” in my elevator speech from now on.

Now, if nothing else, this episode reveals to me how critical it is to embrace serendipity in our work and lives, because Brad’s enthusiasm for my plays dates back several years, to when he was a high school teacher/director in search of projects for his students. He originally had pitched Radium Girls as play for his school, and while it was not selected, he was enough of a fan to use the play as a basis for a class project once he got to Mizzou—and to talk it up with his professors, along with some of my other work.

Our conversations about his current project began with this email in February:

Message: I was hoping you could send me copies of The Good Daughter and an exerpt from The Good Girl is Gone. I’m a PhD student at the university of Missouri, and 1) we’re looking for good new plays by women playwrights, and 2) I’d like to read some more of your work. I’ve been a fan of Radium Girls and Penny Candy for several years, and I might decide to write a paper about your work.

I responded immediately, not only because I am always flattered to come across a genuine fan, but because I spent two years in Columbia, Mo., home to the university’s main campus.

When I saw that email I immediately shot backwards 25 years to the people I worked with at The Columbia Daily Tribune. At the time, I was the business reporter (a laughable assignment for someone who can’t even balance her checkbook) and a deeply confused individual, for reasons that will erupt in a play sometime soon. Columbia was also, sad to say, the high point of my newspaper career, and in an odd twist of fate, the place where I got really interested in writing plays, mainly from having performed in a few with the local community theatre—an activity I embraced as a means of getting out of my apartment and meeting more people around town. I was not much of an actress, but the process of rehearsing for a production meant we dove deeply into a script, and out of that I developed an immediate fascination with, and respect for, the craft of the playwright. I didn’t write any scripts while I was working there—that happened after I left—but there the seeds were planted, not just for my eventual development as a writer, but for several of my plays as well—including The Good Daughter, a play that resonates deeply from the experience in Columbia and in ways that I had not realized as I was writing it.

I immediately sent Brad the scripts he requested, and within a few days, he replied:

Two quick questions:

1) Did The Good Daughter get a Pulitzer nomination for drama? When was that?

2) Do you have any other plays that have characters with notable disabilities? I’m noticing some themes of mental/physical impairment in your plays as they conflict with socially constructed norms, and I think I might write a paper on it. Do you have any personal experience with disability that has influenced your writing?

Thanks,

Brad

And I replied:

Hi Bradley, Good Daughter was nominated for the Pulitzer by a critic for Variety — but it was not a finalist, so it won’t be listed on the website. I have always been ambivalent about whether I should mention that in my bios or not … because a lot of plays get nominations … usually the producers nominate them. Disability in the form of a physical impairment is not something I have direct personal experience with; I have family members who have suffered debilitating illnesses, and several friends with physical disabilities. I think Esther is inspired by a friend of mine who always gave off an air of competence and self-confidence, but I later found out there was a lot more to it. She has spina bifida and has an impaired walk — she gets around, but with some difficulty. She told me once that she thought her mother had a lot of anger at her for being born with a disability. I don’t know if I mentioned to you that I used to live out in Missouri; worked at the Columbia Tribune for a couple of years. One of my assignments took me to a farm auction … where I started talking to a woman who was leaning on crutches. She was pretty friendly and after we talked for a while I asked her how she hurt her foot. She said she had polio as a child — and I took a closer look and saw her left leg was withered–much shorter than the right leg. Then I apologized for being a dolt — but what impressed me was — she was out there, looking for farm equipment. She and her husband ran a farm — and she went about her business on crutches, permanently. So these elements probably went into Esther … and her relationship with her father, his guilt and her resentment at his efforts to protect her by limiting her.

The play premiered at NJ Rep in 2003. Its overarching theme is abandonment—and we will leave that discussion for another day–but the immediate physical world of the play is a family farm, something I knew a little about because, while in Columbia, I covered agriculture—a major industry in that part of the country. Thematically, the play deals with brokenness, and a key figure in the story is Eshter, the “crippled sister,” who emerges as one of the strongest members of the family—defying her father’s perception of her as someone who needs to be protected and sheltered, a girl whose physical disability has rendered her unfit for marriage. As it turns out, one young man does not agree—he finds her beautiful.

I never saw Esther as a metaphor. She actually is an active agent in moving the story along, but there is a clear disconnect between the way she sees herself—and the way her family perceives her. This is a theme that recurs in Dirty Pictures—the perception of an individual with a disability clashes with the reality of that person as a human being struggling with the same powerful drives—and prejudices—as the rest of us. As my actress friend observed, people with disabilities are every bit as attracted to beauty as non-disabled people, but they often are at a disadvantage when it comes to reciprocal attention. That’s the basic action underlying Dirty Pictures, and it’s a rather sad commentary on the rest of us that a play is “subversive” simply because it presents a disabled character in hot pursuit of some sexy time with the man of her heart. But as Brad noted in one of his emails,

I saw something in Judy that was different from other portrayals of disability in theatre and film/TV that was intriguing and empowering, and I just kind of dove into that analysis.

And in his paper he writes:

“In Dirty Pictures, Gregory challenges traditional literary uses of disability as mere metaphor without resorting to the absorption of the “message play” mentality. Throughout the play, Judy rejects victimization and seeks personal empowerment, not trying to “overcome” her disability, but rather to see herself as a whole agent, and by doing so perhaps to make others see her the same way.”

Sounds good to me. So good luck to Brad, and to myself as well. With luck his presentation lifts Dirty Pictures onto the radar for a few directors at the conference.