On Saturday Feb. 23 I crossed something off my bucket list–and was a keynote speaker at the 2013 Theatre in Our Schools Mini-Conference in Richmond, a project of the Virginia membership of the American Alliance for Theatre & Education. Organizer Steven Barker invited me to speak on the topic of incorporating the arts into other core education courses. Here’s what I had to say:

Steven asked me to join you today to think through a most intriguing question: How can we transform STEM to STEAM? Or more to the point how can that missing “A” can be incorporated into—and actually enhance—the teaching of other core subjects?

STEM as we know is an initiative to emphasize SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING, and MATH in the classroom.

For lovers and teachers of the arts—all manner of art—-the fact that music, painting, dance, theatre—even literature—is missing from this initiative is not just an unfortunate oversight, it is troubling evidence of an attitude that pervades our culture, which is that the arts are secondary—extraneous, fluff, unimportant—while science and technology are essentials.

To believe that is to be blind to the role of the arts not just in education but in our very lives. As theatre artists, we know that the arts and humanities are vital to helping young people develop essential skills— not the least of which is the exercise of the imagination. Without the ability to envision, the scientific mind would never think past the world as it exists now in the present.

In a recent essay, Princeton University Professor Danielle Allen reminds us:

“That you can’t do well in math and engineering if you can’t read proficiently, and … reading is the province of courses in literature, language and writing. Nor can you do well in science and technology if you can’t interpret images and develop effective visualizations — skills that are strengthened by courses in art and art history.” And, I would argue—by classes in drama.

We are here today on the proposition that the arts and science are not mutually exclusive disciplines but rather, are all of a piece—painting and geometry, poetry and chemistry, drama and physics, dance and biology, music and calculus—all of these are expressions of our profound human capacity for inquiry, creation, inspiration and exploration.

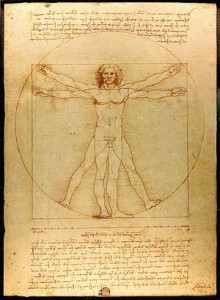

And let us not forget that the artist, like the scientist, deals in questions. Like science, the arts takes the measure of the world around us, but unlike science, they also takes a measure of the world within us. And for this reason helps us all to become more fully human, more reflective, more open, more critical—in our thinking—more confident in our own ideas. This notion that there exists a natural and necessary separation between these fields – and that one is somehow lesser than the other – never occurred to Leonardo Da Vinci – nor to Goethe, a man of letters who was fascinated by science. Anton Chekhov would have been surprised to learn that his degree in medicine disqualified him from writing plays and short stories. We all know that John James Audubon, a pioneer in the field of ornithology, was an accomplished illustrator—today we know him better for his paintings of birds than for his careful observations and documentations of thousands of species. Even Mark Twain was an advocate of scientific inquiry—and a champion of that most useful of inventions, the typewriter.

So we are at a strange juncture in our times—forced to defend the arts, forced to show the value of an essential part of human experience that a generation ago, no one thought to question. Our struggle now is to bring the arts back into the classroom—and integrate them—in our particular case, theatre and drama—into the teaching of other subjects. So I was heartened to see this statement in Virginia’s 2010 Science Standards for grade 5:

Are you ready?

“Musical instruments vibrate to create sound!”

Right there it is: an invitation to any science teacher presenting a lesson in sound waves—as part of the study of force, motion, and energy—to use a musical instrument– a violin, let us say–to show that pitch is the frequency of a vibrating object. A string. Or the teacher might use a series of percussion instruments to demonstrate the concept of amplitude.

I am heartened to read this because if there is room in the science classroom for violins and drums, there is certainly room for us.

And drama has much to offer in rendering science and technology accessible and vital. I know this from personal experience, having written a play, RADIUM GIRLS, about the dialpainters who were poisoned on the job in the 1920s. RADIUM GIRLS is not so much a play about science as a play about capitalism, but the discovery of radium and its commercial and medical applications is central to the story, and so the play becomes a useful study in what happens when an eager corporation—besotted by a brand new technology—ignores the warnings of the scientific community. It is really a play about the exploitation of science for commercial purposes.

You have only to open the newspaper and read about fracking in the Marcellus Shale formation to know how relevant this story is to us today—one hundred years later,

But it is important to keep in mind that in writing this play, I did not set out to teach a lesson about science. I set out to write something that I felt very passionate about; I was drawn to the story of these women and their struggle and I was fascinated by the idea that a miracle cure—an amazing scientific discovery!—could turn out to be the agent of so much destruction.

It is important to keep in mind that while we can use drama to teach lessons about scientific discoveries or technological advancements—we have to remember that the conventions of drama bring their own demands. And first and foremost is that we tell a good story. So when we invite our students to write plays dealing with science or technology, it is critical that we FIND the story first.

And as we know, at the heart of any good story there is always a character on a quest.

Which is what makes science such a ripe area for exploration on stage — because it is all about the inquiry. So I share a few points to keep in mind as we develop these plays:

- First, behind every great breakthrough or discovery are individuals who did not stop searching or questioning. These individuals encountered many barriers—whether the resistance of their peers or community, the limitations of their resources, the failures of early experiments—or their own insecurities. Consider how many times the Wright brothers flopped into the sand at Kitty Hawk before that breathtaking moment on the morning Dec. 17, 1903—when Wilbur Wright flew 800 yards into history. The history of science is full of these stories—stories of failure, persistence, and triumph. So by inviting your students to explore these stories , you are inviting them to relive these discoveries through their own eyes.

- Second, in order to tell these stories, your students will have to research not just the lives of the scientists but the historical context in which these men and women worked. So to write a play about Copernicus your students will need to know not only about the movement of heavenly bodies—but also about the political power of the Roman Catholic Church at the time—and the pressure a scientist might feel to change his story if he thought his immortal soul—or his immediate survival–depended on it. So we need to be open to the idea that we might not always be writing a story of persistence and triumph. It might be a story of persistence and defeat. But whatever it is, the play about a scientist on a quest will always be about so much more than the science alone. So the play about a man who figured out that the Earth revolves around the sun, but later discounted his discovery under pressure from religious interests, is also a play about the intersection of politics and religion, about abuse of power and the limited ability of a single individual to stand up to overt injustice, about all the forces within the life of this man that led him to his capitulation.

- Three, when you invite your students to write these, you must also give them the freedom to invent. It will be inevitable that they have to invent a little if they are going to write any kind of play about historical figures. We all know the famous story of how Isaac Newton discovered gravity when he was hit on the head by an apple—probably apocryphal, but still fun. Only—how did he come to be in that orchard in the first place? And did he eat the apple? You can be sure those questions would come up—and must come up if we were to stage that story. And however your student dramatist chooses to answer those questions—or other questions—the student will have to learn a good deal about Newton to do it. And in the process, the student might stumble onto an even better story. The man who discovered gravity also invented calculus—but he had rivals in this, and they were all in a race for recognition. And that story—of exactly to what a lengths an ambitious man is willing to go to make his name as a scientist—that story has all the elements of a great play.

So this is the stuff of drama—a scientist, a quest, a reason to seek the answer—Fame? Fortune? Impress the wife?—And something vitally important to lose if he—or she—should fail. And my personal sense, having written a two-hour play that draws on 10 years of history and discovery and debate—that involved dozens of medical and scientific figures— is that researching the story can be as exciting as writing it—but when it comes to write it, you must set yourself free. You cannot have a dozen doctors treating five different women; you don’t have time for that on stage. So one doctor stands in for the dozen; one dentist stands in for all the others, and one girl and her friend become the focus of the play—not the five who actually brought the lawsuit. And because I needed to show the terrible loss that this poor young woman endured, I invent a fiancé who dreams of a simple family life that is ultimately denied him because of her illness. And this creates a dramatic tension that pulls the story out of the page—out of the legal transcripts, the notations, and letters on file at the Library of Congress—and creates a relationship that the audience invests and eventually mourns when it ends.

But let me offer this caveat: Yes you can mess with timelines because you will have to, and you can invent characters and you can move a confrontation from the street to the church sanctuary if you need to—that is a dramatist’s prerogative. But my personal sense is that ultimately, you must be true to the outcome and above all, be true to the science — do not mess with the science! — and your story will ring with authenticity.

The other caveat that I would make is that the history of science lends itself to dramatization more readily than scientific principles. It is hard to write a play about gravity, much easier to write a play about the man who discovers it. But we can also write a play in which gravity is a barrier to be broken. As we know, what goes up, must come down—unless it has wings. Then it comes down when it wants to. So how does that character come to take flight? Is it Wilbur Wright? Or someone we never met before—who has figured out another way to be unbound by the forces of nature. Perhaps your students would like to tell that story. It is certainly a play I would love to see.