One of the pleasures of stealing away to a theatre conference such as the American Alliance for Theatre in Education’s (AATE) gathering in Lexington, Ky., last week is meeting theatre artists with a distinctly different view of process.

Such an artist is Steven Barker, who currently teaches at Camp LeJeune High School in North Carolina. Steven outright rejects the Stanislavskiian “get in touch with your emotions” approach to acting in favor of an analysis based in archetype and inspired by the writings of Frankie Armstrong and Janet Rodgers, co-authors of Acting and Singing with the Archetypes.

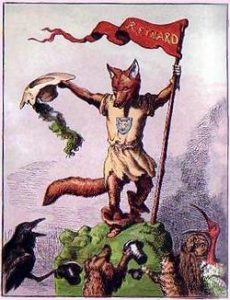

The archetypal figure of the Trickster, or Fool, comes to us not just as the Joker in a card deck, but in the guise of myriad characters whose dominant trait is to embrace joy and shake off restraints imposed by society. Huckleberry Finn comes to mind immediately, as does Pippi Longstocking, and The Cat in the Hat. (Coming off a conference dedicated to theatre for children, I can’t help thinking in terms of childhood literary icons.) And of course we see the Trickster in the cartoon characters of Bugs Bunny, Wile E. Coyote, and Bart Simpson, as well as in Shakespeare’s Puck and Petruchio.

In his workshop at AATE, Steven invited us to get in touch with our inner Trickster—for some that impulse is not buried all the deeply, but for others, the task of awakening him is not so easy. Over the years I’ve grown less inhibited, but not so uninhibited that I don’t balk at kicking off my shoes and strutting around a hotel ballroom clucking like a chicken.

The objective to the exercise is to expose drama teachers to the idea that there is a way to assist young actors in analyzing character that does not require them to dig into deeply personal emotional experiences in search of a sense memory that might apply to a key moment in a play. In Steven’s mind that kind of approach can border on exploitation when you are working with impressionable and often vulnerable young people.

To me the workshop in archetypes presents fascinating possibilities for exploration of character in the creation of plays. How refreshing to break free of the psychological mire that informs so much of American storytelling and focus instead on the outline of character that must be filled in by its opposite. For every archetype has its shadow after all. The hero is plagued with bouts of cowardice. The Ruler veers toward the Tyrant. The Innocent Child has a bit of a Brat within. And the Caregiver Mother can devolve into an Obsessive Parent.

In charting out the psycho-biographies of new characters I find myself falling into the usual preoccupation with childhood traumas, trivial biographical details and hints of emotional upheavals that must surely inform the present action. How much more interesting might it be to chart character based on the qualities of the archetype. The Magician, for example, is on a quest to transform, but his fear is that he will be transformed in the process. Let us transplant the Magician to a cocktail party in the D.C. suburbs and see how this woman works on the Trickster next to her, whose quest is to enjoy life for its own sake but who fears that he might not really be living at all. What kind of fireworks will fly?

Steven informs me that Frankie and Darien will conduct a teacher training workshop next summer on Cape Cod that will incorporate voice, body, and imagination, to explore archetypal journeys and, in their words, “apply the work to text.” Interested parties should contact Janet Rodgers at jrodgers@vcu.edu.

Steven, a trained chef, will be doing the cooking. Perhaps I’ll see you there?